“The Numbers Speak for Themselves”: Tuition Cost Rises Faster than Inflation, Doubles Since 1995

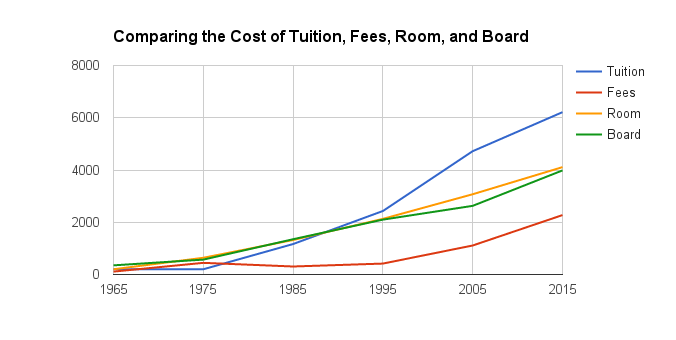

The annual cost of tuition at Frostburg State University has more than doubled since 1995, increasing from $2,431 to $6,214.

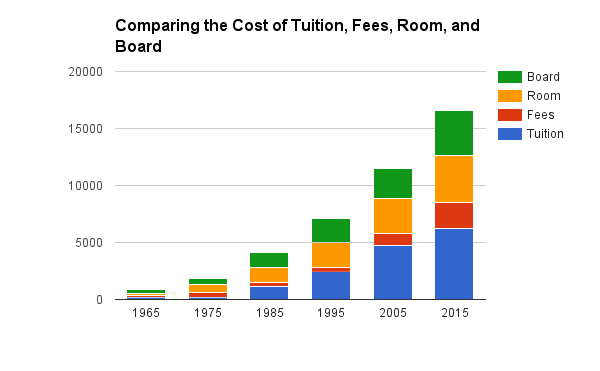

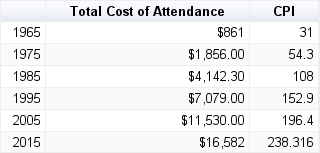

The annual total cost of attendance for a full-time Maryland resident – including tuition, fees, room, and board – has also doubled, rising from $7,079 in 1995 to $16,582 today. The cost has increased by 43.8 percent from $11,530 in the last ten years.

Room and board has nearly doubled, too, increasing from $4,230 in 1995 to $8,094.

In order to determine the cost of room and board for each year, The Bottom Line used the cost of a double room in FSU’s residence halls and the cost of a 14 meal per week plan.

Tuition is increasing at the fastest rate, having increased by 3,107 percent since 1965. Until the late 1980’s, the cost of tuition was less than the individual cost of room or board. Whereas the costs of room and board have increased at a similar, steady rate, tuition began to skyrocket in the 1990’s.

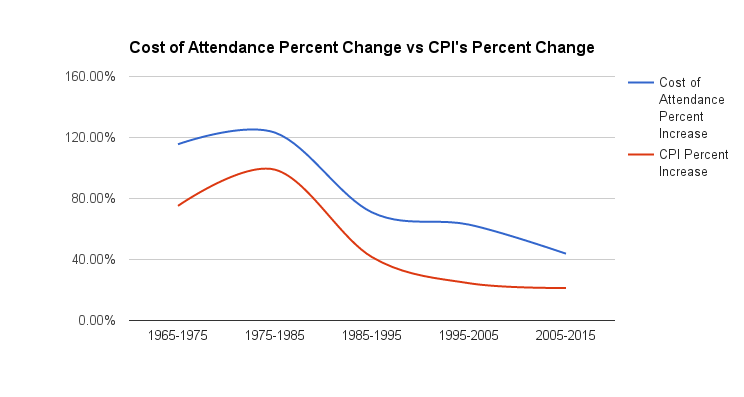

Paying for that cost is increasingly difficult for students, as the cost of tuition is increasing at a much faster rate than the consumer price index (CPI), which is essentially a consumer’s buying power. CPI is used as a measure of inflation.

Since 1965, the cost of attendance has increased 2.5 times faster than the CPI, essentially meaning that the cost of tuition is increasing faster than the value of the U.S. dollar.

“You can’t do what they did in the 60’s and work your way through college,” said Dr. Suzanne McCoskey, an economics professor at FSU.

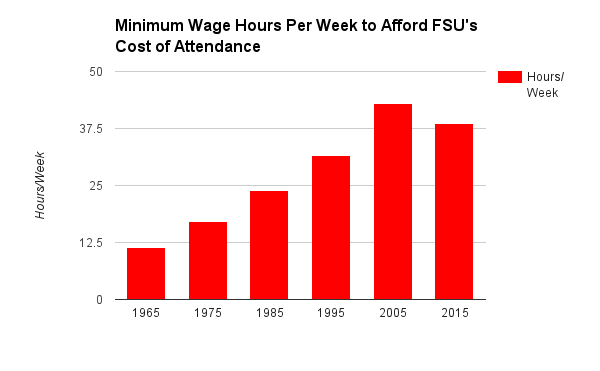

In 1965, when FSU’s cost of attendance was $861 and the minimum wage was $1.25, a student would have to work an average of 11.5 hours a week throughout the year to afford the cost of attendance at FSU.

Now, in 2015, a student would have to work nearly 39 hours a week – one hour shy of fulltime – at the $8.25 minimum wage in order to afford FSU’s $16,582 cost of attendance. Students employed by FSU are limited to only 20 hours a week.

Administrative officials, including David Rose, FSU’s vice president for administration and finance, assert that the price of higher education is being driven higher by the need to compete with other universities for students.

“I think that [competition] is a part of it,” said Rose. “We have to make sure that the university is providing sufficient services. There’s increased demand in counseling services. There’s increased demand in Brady Health. There’s increased demand in marketing our school. We didn’t have to market as much as we used to, you know, to get enrollment.”

Rose said that the need to recruit students has increased, as there are more schools competing for fewer students today in the Mid-Atlantic region. “When I first came here, we did very little recruitment,” he said. “The number of students in the pool has diminished. Demographics have changed. We’re competing with a lot more people, for a lot less students.”

Universities are also spending more money on providing remedial help for students who come into college relatively unprepared, according to Phyllis Reese, the director of communications for the Maryland Higher Education Commission.

Reese explained, “Recent English and Math test scores among Maryland’s K-12 students have dropped for many reasons; but the trend is that colleges and universities have to now invest more funds into remedial help for many students with those deficiencies entering colleges.”

“More staff have to be hired and more resources allocated to help those students adjust to the rigor of postsecondary education and to mentor them to assist them to stay in school and to help assure that they graduate,” she continued. “Each postsecondary institution has its unique methodology in dealing with this on-going trend; and its trends such as this example, that make costs spiral.”

Oftentimes, students declare a major when they go to a college, and then they end up changing their major later in their career.

“When that happens, often, credits are not transferable and as a result, instead of a four-year education, students may graduate in six years, which is another factor in rising costs,” Reese said.

Another factor driving costs higher, McCoskey said, is that in the U.S., universities are spending considerably more money on building community. “If you are [a student] in Europe, a university does one thing: have classes,” she said. “Here in the U.S., our universities have developed into providing our students with communities.”

“Now, universities want state-of-the-art gyms and stadiums,” said McCoskey. “We compete for students, so dorms have to be pristine.”

“One of the things we do in the U.S. that other countries don’t is, when we have universities, we want to have community, and that costs, too,” said McCoskey, who, as a developmental economist, studies and compares international economies. “All the athletic teams, the extracurricular clubs, the new gym facility, etc.”

“Objectively, I think the numbers speak for themselves. I think what’s happening is that universities are starting to take on more social projects. Students are going to pay for that cost,” she said.

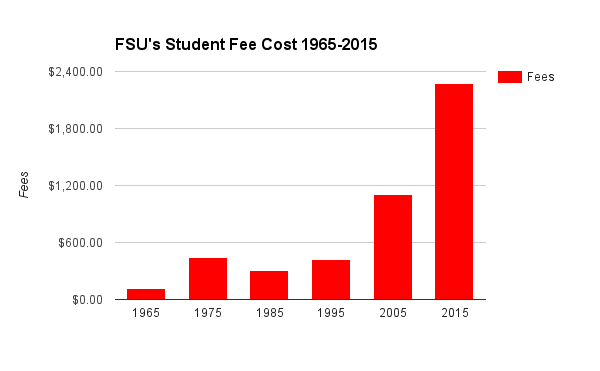

The social and “communal” parts of the university are funded by student fees, not tuition. Since 2005, student fees have doubled from $1,110 to $2,274.

Experts also attribute the rising costs to what is called the “administrative bloat,” the idea that universities are spending increasingly more money on administrative and staff positions that aren’t teaching students in the classroom.

“Critics of higher education often blame faculty salaries for rising costs,” said Dr. Rudy Fichtenbaum in “How to Get College Tuition Under Control,” an article published by the Wall Street Journal. “However, when measured in constant dollars, salaries for full-time faculty at public institutions have actually declined. What is driving costs is the metastasizing army of administrators with bloated salaries, and our university presidents who are now paid as though they were CEOs running a business—and not a very successful one at that,” continued Fichtenbaum, who teaches at Wright State University.

According to salary data provided by FSU officials, the university has 204 exempt staff employees – primarily administrative and staff positions – and 234 full time faculty members. This is nearly a 1:1 ratio. The average salary for an exempt staff employee is $69,575. The average salary for a full time faculty member is $75,291.

The ten highest paid employees at FSU are all in administrative or staff positions. The highest paid faculty member, Dr. Stephen Simpson, previously served as FSU’s Provost for 12 consecutive years. The second highest paid faculty member, Dr. William Childs, also served as FSU’s Provost for two years.

Of the top 20 highest paid employees, only three are faculty members.

Explaining that the university also provides many more services than it used to, Rose said, “We have higher demands then we used to have. We’re not increasing staff just for the sake of increasing staff.”

Although expenses in higher education are drastically increasing, FSU officials say that state funding for higher education is on the decline, forcing the university to put the load on the students’ backs.

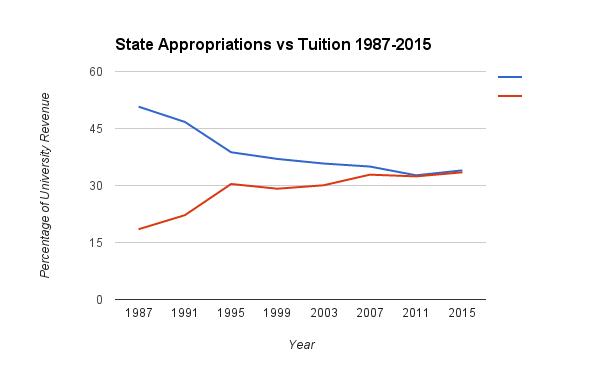

Rose elaborated, saying, “In 87, state appropriations were 51 percent of the budget. It’s now 34. So how do you make up for that loss in state appropriations? You raise tuition. In 87, [tuition] was 17 percent of our total budget. It’s now 33.”

“Particularly in these years, 2005-2015, it’s the change in state appropriations that’s driving that change,” Rose said.

“States don’t fund higher education the way they used to, and it has to be made up somewhere,” Rose said. “Unfortunately, it’s on the backs of the students.”

Reese, a spokesperson for the Maryland Higher Education Commission, did not comment on the decline in state appropriations, when asked by The Bottom Line.

However, she did say that, “During FY 2014, alone, our Office of Student Financial Aid (OSFA) processed and awarded over $118 million to scholarship recipients. Also in the same year, over $400 million in State funds was allocated to community colleges; private nonprofit colleges and universities; historic black colleges and universities; and, regional higher education centers.”

“Many states have the philosophy that you should pay for what you’re getting,” Rose said. “There are people that would argue that state support should go away and be market driven.”

McCoskey echoed this argument. “There are social benefits to having an educated population, for sure, but in terms of income, because students see that benefit themselves, I think they should pay for some of it,” she said.

Many taxpayers who subsidize higher education will not see a direct, personal benefit from it. “I’m not sure it’s fair to have a plumber educate someone who’s going to be a lawyer,” McCoskey said.

“While states funding universities is a really nice social thing to do, it also has a regressive element to it, too, in that it’s paid for out of tax payments from, in some cases, people who never went to college,” she argued. “It makes economic sense that students have to pay for part of their education. In Europe, what I think universities do, they actually transfer benefits from middle class people, to people who will become doctors. And I’m not sure that that’s actually fair.”

Some argue that a better-educated workforce is a social good that’s worth investing in.

“The reality is that we all benefit from an educated workforce, even if the students pay for the bulk of it,” said Tim Magrath, a lecturer in the political science department and former Capitol Hill staffer. “Historically, we saw that an educated work force made us, basically, the most powerful nation in the world. Our education led to innovation, our innovation led to goods and services, and goods and services led to increased gross domestic product and consumption.”

Magrath, who worked for 11 years as a staffer in the Senate and 14 years as a staffer in the House of Representatives, said this phenomenon is caused in part by the “anti-tax wave” brought in by President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. Taxes were drastically cut during Reagan’s administration, and this resulted in a significant revenue decline.

“He basically cut taxes,” Magrath said on Reagan’s presidency. “The burden at the time was on the very wealthy, and he cut the tax rate in our country from close to 79-80 percent on upper income down to 35 percent.”

Magrath said that, “there’s been a wave in Republican politics especially, led by Grover Norquist, who’s got 98 percent of Republicans signing a pledge that they will not increase taxes under any circumstances.” This has led to a decrease in state revenues.

The anti-tax wave hit Frostburg hard in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Between 1987 and 1991, state support for FSU’s budget dropped from 50.74 percent to 46.73 percent. Between 1991 and 1995, state support dropped nearly eight percent, but 46.73 percent down to 38.75 percent. In this time period, tuition increased a little over eight percent, from supporting 22.19 percent of the budget up to 30.4 percent.

These changes occurred during the terms of Governor William Donald Schaffer (1987-1995) and Governor Parris Glendening (1995-2003).

“Now Bob Erlich, governor of Maryland, when he came into office [in 2003], he was one of those that signed the pledge” to not increase taxes, Magarath said. “Just to be fair to Erlich, he inherited what they call a structural deficit.”

“The governor before Erlich cut taxes,” he added. “It’s easy to cut taxes. It’s like pouring water down a hill. Everyone wants tax cuts. But to actually raise taxes is painful, politically.”

When tax revenue is cut, it has to be made up, and ultimately, it has to come from students.

Education often gets the brunt of the cuts because of the lower voter turnout among young voters, Magrath said. “[Politicians] are thinking ‘if we have to make the cuts, who’s going to punish us more?’ If they’re not raising revenue, they’re cutting programs. And the easiest cuts they can make, politically, are those who don’t vote as much,” Magrath explained. “Right now, seniors vote at practically three times the rate that young people vote,” he added.

“I think if you see young people vote, you’ll see priorities change in government,” he said.

Because higher education is such a labor-intensive industry, it’s difficult to cut expenses. “There’s little places that they can cut [in higher education],” Magrath said. “There are administrative staff and so forth that they cut, and I think that universities do that, but the reality they face is that there are expenses that need to be met, and those expenses in some cases are fixed. There’s not much room to adjust it.”

“Education, and an educated workforce, benefits everybody,” Magrath said. “And I guess most people have lost sight of that to a certain degree.”

1 Comment